- Home

- Yoram Kaniuk

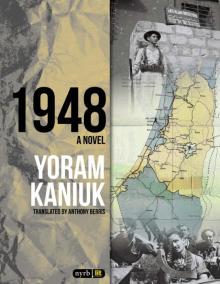

1948

1948 Read online

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright © 2010 Yoram Kaniuk

English translation © 2012 Yoram Kaniuk

Published by arrangement with The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher.

Cover art: Israel Government Press Office and Zoltan Kluger

Cover design: Ian Durovic Stewart

eISBN: 978-1-59017-648-1

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Lit series, visit www.nyrb.com

v3.1

For my dead and living comrades from the Harel Brigade, and for Hanoch Kosovsky, a valiant warrior, who loves who I am and looks askance at me, a man of this land, a bloodthirsty man, like all of us. With profound love for all who were there in the hell of slaughter, and yes, who also established a state.

And when I passed by thee, and saw thee polluted in thine own blood, I said unto thee when thou wast in thy blood, Live; yea I said unto thee when thou wast in thy blood, Live.

—Ezekiel 16:6

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Epilogue

Glossary

About the Author and Translator

One

Whether or not it happened, one way or another, no memory has a country, no country has a memory. I can remember or invent a memory, and at the same time invent a country or think that in the past it was different. There is no country that can be different if it was first not different.

Most important of all is whether it is true that the confused man at the hospital did actually tell me, from the depths of his bitter weeping and without me asking, that everything in life and perhaps in death too (even though he admitted that he hadn’t yet been there) is based on three fundamentals: vengeance, betrayal, and envy. I asked him what about love, and he replied, Love—only when it’s betrayed or in fun. Love comes after betrayal, but with you it will come beforehand.

I thought I’d write a book quite the reverse of a laudable one and call it “The Funniest Thing that Happened to Me in the War.” In the end I wrote it under this other name, 1948, which isn’t at all funny, because I truly wanted to write about the funniest thing that happened to me in the war.

Right after the conversation with the confused man at the entrance to the hospital in bombarded Jerusalem, which was an Italian monastery converted into an abattoir for soldiers, I was laid on a real bed and was flooded with pleasure, because after all those months I was lying on a sheet. My leg hurt a lot, but once I settled in I felt good, the sheet touched my back, a glass of water stood beside the bed and I drank from it, and just as I began feeling like a human being once more, there was a sudden loud noise, the ceiling collapsed from a shell that sliced through it, its hanging innards began falling like jets of snot, and two nuns hurried to me, got me onto a stretcher, and on the way to the cellar I was covered with ancient Christian plaster that continued to drizzle from the ceiling. The sister looked at me, I was half naked, and in Germanic Hebrew she said that attempting to prevail over Satan was like a spark from hell falling onto the soul’s wedding dress. According to Ben-Azzai—that’s what she said, I remember!—according to Ben-Azzai, “My soul thirsts for Torah, and the preservation of the world is in the hands of others.”

There was a connection there. I was young. She was young. I was half naked. She was dressed as a nun. But she had decided to be a virgin whereas I was forced to be one, and she, I don’t remember why, went on to say that the doctors are playing God! I evidently do remember, because it’s impossible to remember the terrible pain, but I remember that it hurt. The nuns put me down, covered in dust, this time onto a mattress without a sheet. For some reason I laughed, and one of the nuns—who because it is said that there is no humor in heaven had never heard laughter, and didn’t know exactly what this sound coming from me was, and why my face had suddenly opened—cleaned me up thoroughly and asked what I was thinking when I turned up my mouth like that. She spoke Hebrew quite fluently, and I replied that I just, I don’t think, I just do it. She said, But you look like someone who knows how to think, and I told her that maybe I’d try thinking, and she said, You know, you’re a sweet man. And then she stopped short because she didn’t know what to say to an eighteen-year-old boy about to have a leg amputated. I told her that what made me laugh was that only now, when I wouldn’t be fighting anymore, I realized that I had no idea in which war I’d been fighting and what exactly had happened to me in that war and why I’d carried on fighting when the chances of my getting back home were nil. I told her I understand that I don’t exactly know who I am. That I don’t know what I’m doing and don’t know where I’ve been. After she laid me down on the stinking mattress in the cellar that was gradually filling up with the wounded, she ran into the corridor to fetch somebody else.

Throughout the days of the fighting I didn’t think. I didn’t make plans. I did what I was told and took initiative only when there was no choice and we had to improvise. I was told to sleep, I slept. I was told to get up, I got up. They gave out food, I ate. When they didn’t, I wasn’t hungry. It was evidently true that they put sodium bicarbonate in the small quantity of water we were given to drink because I didn’t think about girls, who a year earlier had devoured me with their budding femininity. I remembered that there had been absolutely nothing inside my battered skull. We were like kids, so shamefully young, volunteers, we were boors, partisans. Except for me there weren’t any youngsters who had previously worked in youth movements—they would be called up later, after we’d finished establishing a state for them. We were just one from here and another from there, we still had no documents whatsoever, except for Palestinian birth certificates, which of course we didn’t carry with us. So why had I remained in that parched hole and why hadn’t I gone home while the siege had not yet been tightened? Why hadn’t I gone home? After all, nobody would have known what had happened to me and anyway, there was no time to think, and they would surely have assumed I’d been captured by the Jordanians or died and been buried in a forlorn grave “known only to God,” the way the gravestones were inscribed in the field of the dead in Trumpeldor Street in Tel Aviv, and perhaps they’d find my body if I had indeed died someplace where no one imagined I’d be.

I was a fool who’d gone off to be a valiant soldier and smite the enemy. That’s what I was. Had I enlisted so early, at seventeen and a half, because I was a hero or was it because I was scared and had run away from something? And if so, from what? I was evidently a coward. People with creative ima

ginations also possess this ability to be fools who volunteer for lost causes. I emerged from my dread as a hero who had overcome his fears. And beforehand I’d been a bundle of fears. Of death. Of the dark. Of people. Of crowds. Of disease-bearing flies, of Anopheles mosquitoes that carry malaria, about which my mother, Sarah, would speak as a woman who’d been personally acquainted with them in her youth in Palestine. I wasn’t a courageous hero like many of the troops. I was somebody who didn’t give up. Somebody who, although frightened, saw death and did not flinch. I knew that aboard the small ships at sea there were thousands of homeless Holocaust survivors unwanted by any country, and I’d read that three years earlier Herr Goebbels had said that if the Jews were so clever and so talented, and played so beautifully, how was it that no country wanted them, and I remember it sticking in my craw and I wanted to take part in bringing those Jews here.

Was that truly the real reason I enlisted in November 1947, a short time before the United Nations resolution on the partition of Palestine? What I do remember is that one day, in the first semester in twelfth grade at the Tichon Hadash High School, which was the most wonderful place to be, with its stirring principal, Tony Halle, who looked like a magnificent mouse and one day stood on a chair and closed her eyes, with tears oozing from beneath their lids, and with a kind of profound yearning began describing how, in 1077, Heinrich IV stood facing the fortress of Canossa, where Pope Gregory VII was hiding behind a curtain, and how poor Heinrich stood there in the cold, the snow, in a desolate land, how he stood there barefoot, she said with her deep beauty, how he stood without shoes, without socks, without a coat, without a shirt, without underpants, and wept before the pope, who was hiding in warm clothing, and behind him a blazing hearth, and he looked and saw the handsome, heroic Heinrich IV, the magnificent and beloved king, his true love, freezing naked and pleading for his life, and all of us, the whole class, wept at hearing about the fate of Heinrich IV, and one day, just like that, I left that sweet school with an adage that even I didn’t believe, that we wouldn’t drive the British out with cube roots, and I volunteered for the Palyam* because I said I’d bring the survivors to our country’s shores and didn’t really think about where the boats carrying them would come to. Right after our sea training we went off to fight in the Jerusalem and Judean hills. So I’d said I’d enlisted to bring Jews, so what? Did I really think that the boats would reach the Port of Jerusalem that’s buried alive between the desert and the green landscape and Bab el-Wad*? And even before that, our absurd teachers had gone on at us and stuffed our minds with building and being built in the Land of Israel, but we didn’t really understand what it meant. After all, we were born here. With the thistles. With the jackals. With the carts harnessed to blinkered mules, and the prickly pears, and the pomegranates, and the cypresses with their beautiful foliage, so how do you actually build and be built?

Here and there one heard talk of a Jewish state. The concept of “state” didn’t ring true, it didn’t sound real, since when, after two thousand years, had our people had a state? And what kind of a state would it be? What would this little state be like? Liechtenstein, the Congo? And what, would Ben-Gurion wear a top hat and stand on a box like Herzl on the balcony in Basel so as to look tall? And would a Jewish policeman blow a whistle or a shofar, a ritual ram’s horn?

In an old volume hidden behind my father’s German books—highlighted in red ink and written in the cursive Rashi script he liked to use with that latent spark of a Galician Jew who thought he’d been born in Berlin and who sometimes sang Jewish prayers between Schubert and Brahms lieder—I found the story about the Rabbi of Ladi who fought a historic battle with the Rabbi of Konitz over the possible conquest of Moscow by Napoleon. They had to decide, once and for all, whether or not this conquest was good for the Jews, and since the fate of the Jews was about to be sealed, the vigorous Rabbi of Ladi, who was so concerned by the magnitude of the task that tears flowed from his eyes, summoned the Rabbi of Konitz to the synagogue to decide what would be good for the Jews. Something happened, the Rabbi of Ladi was somewhat late and the Rabbi of Konitz got there before him, took his shofar and started to blow it, and the Rabbi of Ladi ran inside, snatched the shofar from his hands together with the blast from the Rabbi of Konitz’s shofar, and that’s what caused Napoleon’s defeat at Moscow and decided the fate of the Jews.

That’s what happened to us. We went off to bring Jews by sea and ended up establishing a state in the Jerusalem hills. It’s a mistake to think that we fought for the establishment of this state. How were we to know how you establish a state? Had anybody done it before us? Nonsense, a Jewish state was the blast snatched from the shofar of others, and yes, somehow with the power of a miracle that was actually the act, the sound of the shofar reached its destination. For when the Palmach* took Safed (I wasn’t there), the town’s rabbi said that Safed had been saved by a miracle and deeds: the deeds were prayers and the miracle was that the Palmach arrived. We were charged with miracle making. A state was a vague, even ridiculous notion. The first thing we know about the history of our people was the patriarch Abram fleeing from his homeland because he heard God, not Moses’s god but another Canaanite god, say to him, Get thee out of thy country! So how could we know what love of country is? And of all the peoples in the world that didn’t think of fleeing from their homeland for two thousand years, we should suddenly become a people that loves a land of its own, that isn’t its own, and establish a state in it? We’re a people of suitcases, of wandering, of yearning for a place we were never in. Abram comes and finds famine in the land of his dreams and right away goes down to Egypt to sojourn there and returns after a long time, the way an American Israeli of today returns with great wealth from California, for the God of the Hebrews got tired of creating worlds and decided to create a new Hebrew world and started it in heaven and only later it came to Earth, since states do not dwell in heaven. So we’ll build a state of nomads? We—the serfs of the Almighty, whom we despised, for whom “Abroad” was the name of some country, and we only knew about real countries from our stamp collections, and for us, because of the stamps’ size and beauty, Luxembourg was bigger than the United States, and if we’d learned anything about countries we’d learned how to aspire to one but not how to establish it, especially if it were to be created in a hostile region like ours—we would establish it? But what did they say back then when they wanted to play with words? Ha-ikar, bat ha-ikar. Beikar kesheha-ikar eino babayit. (The main thing is the farmer’s daughter. Especially when the farmer’s not home.)

And it must be remembered that with us was that sweet lunatic Benny Marshak, the secular Hasid political commissar who dreamed of a Jewish state, and caught cold from yearning so much for a state, and vilified the enemies of Israel even in his sleep, and who came with us from Caesarea—where we were waiting for the illegal immigrants who didn’t come— to the war in the hills that came with a vengeance, and who’d shout over and over—he knew how to shout—that we should establish a state for him already, and we thought, Poor guy, he loves a nonexistent state, and if it is established, it’ll probably be Afula, which at the time was the only city, even if all its buildings were outside it, and which was actually a bus stop on the way to the Valley of Jezreel or a toilet stop on the road to Haifa. Poor Benny really and truly had waited two thousand years plus a few days, whose duration isn’t written in any ledger. So we went along with him because he hadn’t slept for two months, and we’d checked, we’d spied on him, he really hadn’t slept, eaten, drunk, or washed (we could feel the last item even without spying on him), and all the time he was busy with establishing a state that nobody before him had seen what it looked like, and when he tried to describe it he’d tremble with the tears choking him and yell excitedly. And when he’d had it with all his yearning and we thought that something must really be done about it and a state should be established for Benny so he’d get off our back, we were stuck on some hilltop strongpoint, I don’t remember which, and a good-

looking boy, whose name I’ve forgotten, straightened up for a moment and took a direct hit from a three-inch mortar shell that sliced him, actually sliced him, as if it were a sharp knife, and we saw his body split into two parts that fell to the two sides it had beforehand, when he was good-looking and not a bleeding human salami as he was now. And the blood flowed. We covered him with our long, heavy, woolen army coats, which in belles letters were called greatcoats, and somebody asked who he was, perhaps a new immigrant who’d fallen in with us, and we fell asleep.

It was cold without our greatcoats. We heard sudden shouting. Not shouting, but wild yelling. Somebody came and woke us up in the terrible darkness, and weeping and laughing told us in a hoarse voice that someone had heard on a battery radio that Ben-Gurion had established a state, and then said, Come, let us arise and sing “Hatikva*” (they used forms like that back then), and we told the jerk, Crap! We don’t even know the words, and anyway, where has Ben-Gurion established his state? And he said he’d heard that he’d established it in Tel Aviv, and we said, Look, we’re under siege here, in Jerusalem, we’re in Bab el-Wad and there’s no state here, and Jerusalem isn’t in the State of Tel Aviv, and we fell asleep.

Early the next morning, at four or five, Benny Marshak loomed out of the mist, and we noticed that he looked like he’d shed two thousand years plus a few days. Suddenly he was young, dauntless, and laughing, leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the hills, and singing, and for a moment I thought that even his odor of ancient sweat had dissipated. But he carried on, not even noticing the sliced boy on the ground covered with greatcoats. He stood to attention and stood at ease, his hair tangled, and he tried to sing “Hatikva” and what came out was the hoarseness of an Eretz Yisrael generation which thought that the louder you shout the righter you are. Standing steadfastly, planted in the soil, barely moving, he began dancing a clumsy, heavy-footed hora they’d brought with them from the Diaspora, a hora of Hasidim, and he danced in threadbare khaki pants with a Parabellum-Pistole strapped to his waist, because back then you only trusted God with a gun in your hand, and it was a hora of one man multiplied by two thousand years plus a few days, and he leapt and swayed and yelled, “God will build Galilee / God will build Galilee”; and we told him, We’re in Jerusalem, and one of us, still asleep, suddenly began declaiming the poem: “Man was born to die / The horse was born to foal / If you’ve climbed a pole / Then you’re bound to fall.” And Benny Marshak yells, Insolent rascals, what are you thinking of? This is a historic moment! The most historic moment in two thousand years! And then he suddenly starts crying and we get up and join him. I don’t want to, I’m tired, but Benny is begging and grabs me with a hand that’s strong from forty years in the kibbutz, and in the middle of nowhere, at four or five in the morning, in the asshole of the world, next to a body that had begun to stink, on a pissant hilltop, amid the firing, a few young idiots are dancing and yelling “God will build Galilee” in Jerusalem that had never seen Galilee, yelling “A Jewish state, a Jewish state,” and as we dance I start trembling, my eyes close, I stick matches between my eyebrows and cheeks but fall asleep as I dance, and Benny runs off to tell some other guys. Afterward we carried the sliced guy to Kiryat Anavim*, handed him over to the kibbutz oldsters who were in charge of burials, and slept a while. When we were awakened we were sent off to fight another battle and again we forgot why, and that was the funniest thing that happened to me in that war, that I established a state while asleep and dancing the hora next to an unknown comrade who’d been sliced into two.

Life on Sandpaper

Life on Sandpaper 1948

1948 B002FB6BZK EBOK

B002FB6BZK EBOK